What is This Thing Called "Practice"?

and how the Tree of Contemplative Practices can help you discover yours

Welcome to The Practice of Life — a place to slow down, befriend yourself, and connect with the world from kindness and awareness. If you’re just arriving for the first time, you may appreciate this introduction.

Everything here is freely offered without paywalls. If you appreciate what you find, please consider a free or paid subscription, or a one-time donation. Your financial support creates possibilities for me to spend more time on writing, including a memoir-in-progress. It also really helps if you give this post a ‘like’ (click the heart at the end) and share it. Thank you!

We are living through exceptionally challenging times. In addition to having a sense of possibility about what humans have done in response to past challenging times (the focus of my last post, We Are the Ones We’ve Been Waiting For), it greatly helps to have some kind of practice that cultivates resilience, equanimity, compassion, and even joy.

I often use the word “practice” and it’s central to the title of this Substack publication. But what exactly does this mean?

First, let me share my personal definition of practice:

An activity that you do on a regular basis (ideally each day) that helps you to cultivate a sense of self-awareness, joy, equanimity, resilience, and compassion for yourself and others.

To me, a practice is about being in an intentional relationship with that activity (and sometimes it’s a person or experience) and being willing to learn about yourself and the world in that process.

Even though I’m using the word in a spiritual context, “practice” is a fine word choice for other reasons. Think of sitting down at a piano and working on the same scale over and over. The idea is to get the feel of those notes in your bones so you get to a point where music flows out of you rather than having to think of what you’re playing. In the case of a spiritual practice, the intention is to become so attuned to our inner wisdom that we’re living from a place of awareness rather than ignorance, if not all at least most of the time.

The word also reminds us that this is something we need to do throughout our whole life. There is never an endpoint. We are really practicing the art of being human.

Practice is not synonymous with sitting meditation, although it is certainly one of its forms. I really started to understand this when I was research director at the Center for Contemplative Mind in Society from 2002 to 2004. The organization, which has now sun-setted, did wonderful work to shine a light on the many ways that contemplative practices from diverse religious and spiritual traditions were turning up in education, healthcare, business, law, activism, and other secular settings. The Center helped to put “mindfulness” on the map before it became a buzzword.

As a way to summarize the findings from a qualitative research project that I directed called “The Contemplative Net,” I came up with the Tree of Contemplative Practices, a visual model to illustrate the diverse forms of practice that we heard about from interviewees, who included Jon Kabat-Zinn, Angeles Arrien, Bernie Glassman, Joan Halifax, Father Thomas Keating, Rabbi Zalman Schacter-Shalomi, and

. One of the big themes that came through in the interviews was “meeting people where they were at.”Each branch of the Tree represents a grouping of practices, as the interviewees described them. Stillness Practices focus on quieting the mind and body in order to develop calmness and focus. Sitting meditation lands on this branch. Generative Practices come in many different forms but shared the common intention of generating certain qualities such as devotion or compassion. One example of a Generative Practice is Metta practice, which cultivates lovingkindness.

Most importantly, the roots at the base of the Tree represent the two intentions all these diverse practices have in common: to cultivate Connection with something bigger than yourself (that might be the Divine however you define that, nature) and Awareness.

What I love about the Tree and what people have found so helpful is that it offers a wide variety of practices to consider and choose from. The Tree can help us see that it’s really the intention that matters most in a practice, not so much the form that it comes in. It can be easy to get caught up in the idea that we aren’t good at sitting meditation and then give up on the possibility that we can have a practice at all. The Tree allows people to understand that practice can take many different forms, and some might be a better fit for us than others. As one woman said, “It was a revelation to me that meditation wasn’t the only way. Choosing a different branch enabled me to finally find a practice that worked for me.”

The Tree also allows room for creativity. Whenever I share it, I emphasize that it’s a living document, one that people can add onto or change in a way that speaks to them. In workshops, I give participants a blank version so they can create their own.

The Tree was never meant to be a definitive taxonomy but rather an invitation to explore what practice means to each of us. One woman shared that during a personal retreat day, she added a branch for “Food Meditation” which she described as “engaging in awareness with each step in my meal preparation.” She told me that this helped her to shift away from an old habit of rushing to eat when she worked on chaotic film sets.

The Tree has taught me something about my own practice as well. It’s helped me to understand that while zazen (sitting meditation in the Zen tradition) is fundamental in my life, practice shows up in other ways. I’ve learned that if I don’t mix in some walking and writing practice in the course of a day, I can get a little wonky.

You can take many activities in your life and transform them into a practice by considering the roots on the Tree. How can you enter into that activity with an intention to raise your self-awareness – to see into lifelong patterns that have perhaps not served you – and to connect with something bigger than yourself?

Practices like meditation, yoga, and chanting all offer those opportunities. But it can also be true for things you love doing like knitting, running, cooking, and gardening (just to name a few examples). The key is to devote yourself to that activity on a regular basis, and to enter into a relationship with it where you are willing to grow your consciousness and awareness.

That may not always be comfortable. You’re going to bump up against your own least-helpful tendencies and, in the light of awareness, that may not feel good.

Perhaps you’re immersed in your garden. You’ve spent months preparing your soil, tending to the seedlings, watering the plants as they grow. There’s the blissful part of practice – all these ingredients support you to connect more deeply with yourself and with the earth. Then at the end of this cycle, a deer wanders into your garden and enjoys eating your beautiful heads of lettuce before you have a chance to harvest them. Right there is the practice opportunity. What feeling arises for you, and what do you do with that feeling? That’s the choice point. We can blindly react with frustration, even anger. Or we can take it as an invitation to practice with and accept and even appreciate the truth of impermanence.

That’s the true gift of a practice: to realize that the choice is always ours, though we often don’t realize it.

Right now, my practice is being present to my canine companion, Lucy, who has been in my life 16 years. As a rescue dog, her age has always been somewhat of a mystery. She is at least 17, because she had puppies the year she arrived. She could be 18, 19, who knows, maybe even 20. Her aging process has been a lot more noticeable lately. She’s lost her hearing and sometimes I wonder how well she can see when she bumps into a trash can on our walk. At times she’s confused, at times anxious. She’s not the same spirited dog that I’ve known all these years though there are moments when that spirit still shines through.

Every day, I get up and take her for a walk, get her meals together, and keep an eye on her for other needs that might be arising. Every single day.

There are days I don’t feel like doing this. Days I’d rather be solely focused on myself. Days that she seems especially lost and confused, and I feel sad. Days I feel resentful that I can’t just pick up and go travel somewhere without the arduous task of finding a good dog sitter. That kind of spontaneity has been missing from my life for quite some time, and I rub up against it.

All of this is my practice point. I draw on years of zazen to help me tap into the inner strength I need to continue to be in good relationship with this challenge, and even to see it as a gift. A consistent and deep practice can help transform the most difficult situation into a portal for awakening. That includes the one we’re collectively in right now.

To sum up, these are all elements of practice:

Being in relationship with a being or an activity, over time

Holding the intention to notice what arises in myself in the context of that relationship

Be willing to learn from this experience rather than react to it

I’d love to hear from you….

What are the practices that nourish you on a daily or near-daily basis?

What gifts have you harvested from your practice?

Do you see anything on the Tree that you’re interested in trying out?

ANNOUNCEMENTS

WORK WITH ME ONE-TO-ONE

My Guidance and Encouragement (G+E) sessions are a unique blend of mentoring, resource connections, and spiritual guidance customized to your needs. G+E sessions are especially useful when you’re in a transitional time (shifting careers, changes in relationships, moving to a new area, etc.) and seeking support to navigate these changes in the most beneficial way. G+E sessions are also about walking with you as you find your way through these transformational times. Something more beautiful is waiting on the other side for all of us, I have faith in that. These sessions are a means of co-creating that future.

Founding members of The Practice of Life receive a complimentary G+E session each year, but these sessions are available to everyone on a sliding scale basis.

POSTCARDS FROM NEW MEXICO

I’ve got another Substack newsletter, very different than this one! If you have a warm spot in your heart for all things New Mexico, you might enjoy checking out Postcards from New Mexico.

LOOKING FOR SUPPORT TO CREATE RIGHT LIVELIHOOD?

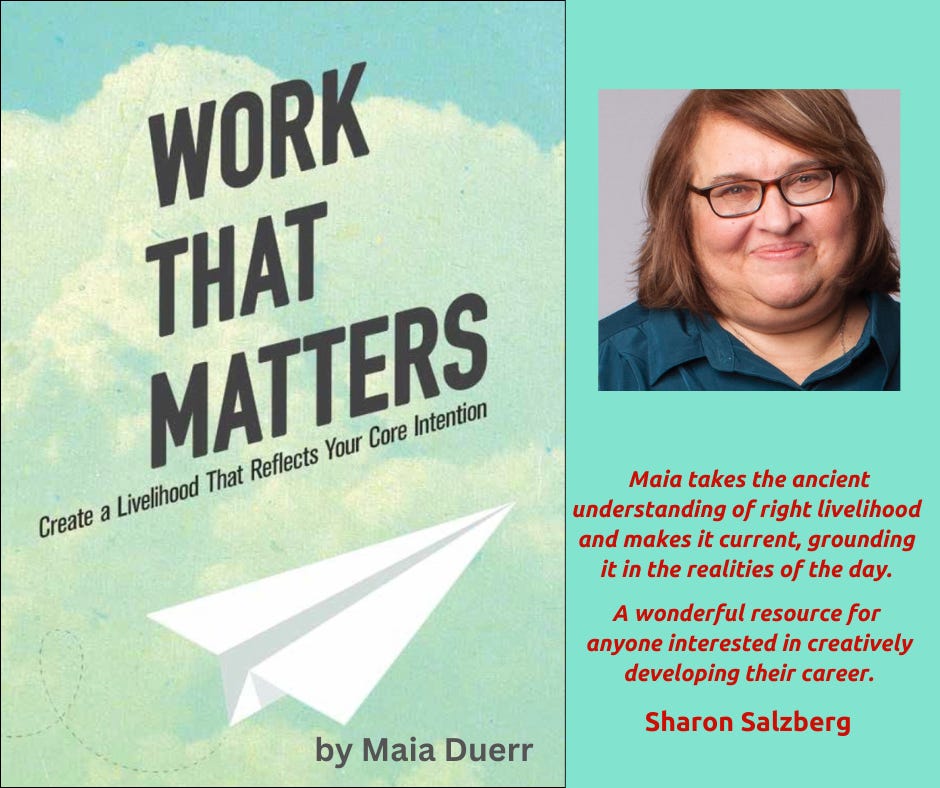

Check out my book Work That Matters: Create a Livelihood that Reflects Your Core Intention (Parallax Press, 2017)

You’ve posted the Tree of Contemplative Practices before, but for some reason, it hits me differently today. (Well, it’s because I’m different than that person who first saw it, more receptive). Tricycle Magazine, in their “interview with a contemplative” section, used to always ask something like: “how long have you gone without practicing?” I thought that an odd question—initially provoking guilt in me if I missed a day of zazen. And then I began to think the question went much deeper; maybe some kind of test of the person’s understanding of the word/concept of practice (“test” is too strong a word, I don’t think Tricycle plays “gotcha” like that.) Now, and affirmed by your writing on this important aspect of humanness, were I to be asked that question, I’d say something like: “I’ve never stopped. I’m almost 60 years old and I now believe I’ve been practicing for almost 60 years…and maybe longer.” And with words like yours, Maia, I know that’s an authentic, if indeed valuable, way to integrate practice into a human life. I’m a new grandpa, and I see the little guru that my grandson is, he has a great practice going—when he drinks mother’s milk, there’s just drinking of mother’s milk; when he’s sleeping, there’s just sleeping; when he’s awake, he’s just in the present moment because he has no conception of past or future. Oh, and when he’s poopy, there’s just poop. (LOL!) I now aspire my practice to be like my grandson’s practice. Pure, joyful, effortless…just this. Only this. And now this too.

Thank you for this, Maia.

You writing makes me reconsider the way the word "practice" has been commonly used in the Western mind, particularly in the adage, "practice makes perfect."

On some level, I've always held the idea of "practice" as a means to an end--if I do something with enough focus and dedication, there will come a day when I am so accomplished it, I will no longer need to "practice"--I'll be a master. I just "do" it. Or worse, maybe I'll rest on my laurels and stop doing it altogether.Done that, been there. Checked off my list. A very Western, goal-oriented, transactional perspective.

Your writing questions this hubristic desire to practice as a means to achieve perfection. Yes, we should strive for excellence and a degree of mastery, but never to become "perfect." There's no growth in perfection. No life.